Schrödinger 1931, Wasserstein 1969, Lipman 2022

Joys of wandering through NeurIPS 2025 poster sessions. From Earth Mover's Distance, to cloud particles.

One of the delightful surprises of walking through a conference poster session is how often a completely new solution to a modern problem traces its roots back to an idea that is anything but new. Machine learning is filled with deep classical origins. Today I learned about the Schrödinger bridge, thanks to an illuminating conversation with Tao Zhong, author of Grasp2Grasp. Introduced in 1931 as a way to reason about the most likely evolution of a cloud of particles, it’s a powerful tool for adapting one probability distribution into another. Together with KL divergence and flow matching, it forms a kind of conceptual tripod that lets us describe how probability mass can drift, bend, and reshape itself in principled ways.

Moving sand and measuring effort, Earth Mover’s Distance

EMD takes me back to the early 2010s when I used it as a color perceptual similarity proxy for apparel images. Say you have a tray with a pile of sand shaped like a hill on the left. Next to it, a photo of how you want the sand to look, maybe a smaller hill on the right, or two bumps instead of one.

You hire a tiny construction crew with toy shovels. Their job is to move the sand until the real pile matches the picture. Every time they move a bit of sand, they pay a cost that depends on how far they moved it.

Move a lot of sand a long way: expensive.

Move a little sand a short way: cheap.

The Earth Mover’s Distance is simply the minimum total effort they need to reshape pile A into pile B. How hard is it to rearrange this into that. For my apparel project we moved pixels in RGB space.

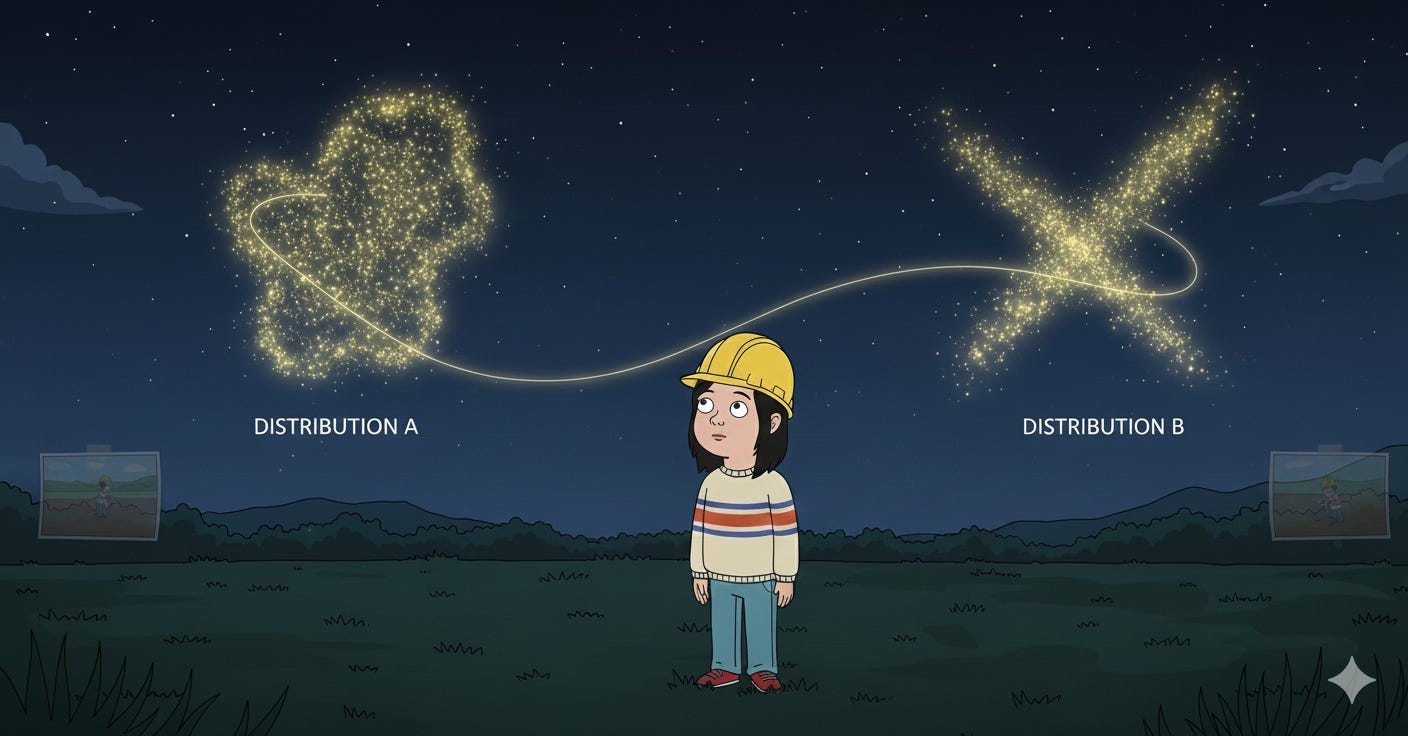

Mathematicians reuse this idea for probability distributions. Instead of sand grains, you think of “mass” that says how likely something is, for example where people live in a city, or which pixels are bright in an image.

From sand to drifting fireflies, Schrödinger Bridge

Swap sand for glowing fireflies, introducing chaotic movement. You look up at a field at night. In the first long exposure photo, most fireflies are on the left. In the second photo, taken later, most are on the right. You know that in between they mostly float around randomly in a gentle breeze.

So you ask a new question: given that fireflies usually wander in a simple random way, what is the most likely story of how they moved between photo 1 and photo 2?

The Schrödinger Bridge asks for the most natural and likely random motion that could turn distribution A into distribution B while staying as close as possible to normal drifting. You do not get a single “move this grain there” plan, you get a whole movie of how a cloud can realistically morph over time.

Teaching the computer how to model wind, Flow Matching

Flow matching is a new technique, powerfully enhancing modern generative models. Imagine the sky full of tiny droplets floating everywhere at random. You know that it’s possible for wind and water to organize into a cloud that’s shaped like an elephant. To do this, we teach a model the right way for droplets to move. At every point in the sky and at every moment, there is a tiny arrow telling a droplet which way to drift. We learn these arrows by picking a random droplet and a real elephant droplet, drawing a simple path between them, and telling the model what the motion along that path should look like.

Here we are doing something similar to EMD. After seeing many such examples, the model learns how the whole wind should behave. When we start with new random droplets and let them follow the learned wind from start to finish, they drift into place and form a fresh elephant cloud.